Baroque Oil Painting: 6 Masters Who Defined Drama (Their Shocking Masterpieces Explained)

The Baroque era (c. 1600–1750) wasn’t just an art movement—it was a revolution of emotion. After the Renaissance’s focus on balance and order, Baroque Artists turned to drama: bold shadows, swirling movement, and raw feeling. Oil painting became their weapon, letting them create scenes that feel like they’re exploding off the canvas. At theArtPaint, we’re unpacking how Baroque oil painting evolved, the geniuses behind it, and the masterpieces that still make us gasp.

The Baroque Shift: Why Oil Became a Tool for Drama

Renaissance art aimed for harmony; Baroque art aimed for reaction. Artists wanted viewers to gasp, weep, or feel awe. Oil paint was perfect for this: its slow drying time let them build extreme light-dark contrasts (called “chiaroscuro”), blend emotions into skin, and layer textures for chaos or grandeur.

Patrons—from the Catholic Church to wealthy kings—loved it. The Church used Baroque oil paintings to reenergize faith after the Reformation; rulers used them to show power. This demand pushed artists to experiment, turning oil into a medium of storytelling unlike any before.

6 Defining Baroque Oil Painters & Their Iconic Works

1. Caravaggio (1571–1610): The God of Shadows

Caravaggio didn’t just paint—he staged dramas. His “tenebrism” (extreme chiaroscuro) threw most of the canvas into blackness, making a single beam of light feel like a spotlight on the action.

Masterpiece: The Calling of St. Matthew (1599–1600). Oil lets him turn a dark tavern into a theater. Christ’s hand (lit by a harsh glow) reaches for Matthew, who looks shocked—his face a mix of confusion and awe, painted with thin oil glazes. The shadows? Thick, tar-like oil mixed with lamp black, making the moment feel urgent, almost dangerous.

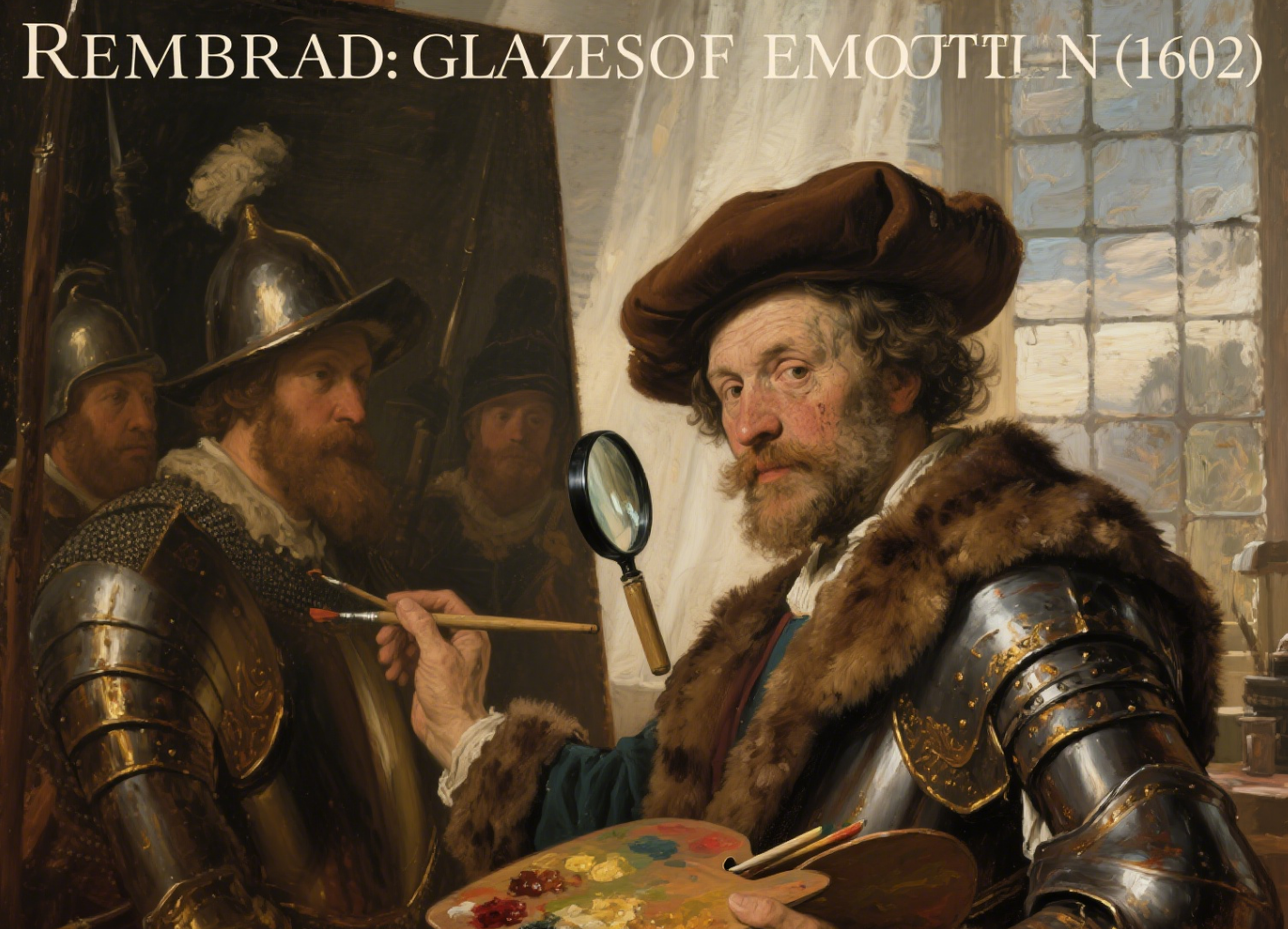

2. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669): Emotion in Every Glaze

Rembrandt used oil to dig into the human soul. He layered glazes (up to 30!) to make skin look lived-in—wrinkled, flushed, or tear-streaked. His portraits aren’t just faces; they’re life stories.

Masterpiece: The Night Watch (1642). This massive oil painting is a riot of movement: a militia marches out, flags wave, a dog barks. Rembrandt uses thick impasto for their shiny armor and soft glazes for their faces—some confident, some scared. He even scraped wet oil with a palette knife to make the flag’s fabric ripple.

3. Diego Velázquez (1599–1660): The King’s Eye

Velázquez, painter to Spain’s King Philip IV, used oil to capture power—quietly. His court portraits feel like secrets: rulers aren’t posed; they’re caught in a moment, with oil making their silk robes heavy and their eyes sharp.

Masterpiece: Las Meninas (1656). This oil painting bends reality: a princess, her maids, and Velázquez himself (painting) stare at us—or maybe the king and queen, whose reflection glows in a mirror. Oil lets him blur the lines between viewer and subject, making us feel like intruders in the royal room.

4. Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640): Chaos in Color

Rubens painted passion—literally. His oil works burst with bodies, fur, and fabric, all swirling in a riot of reds and golds. He mixed oil with resin to make colors pop, even in large canvases.

Masterpiece: The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (1618). This mythological scene is pure energy: two women are carried off by centaurs, their dresses flying. Rubens uses thick, buttery oil for the centaurs’ muscles and thin glazes for the women’s flowing hair, making the chaos feel both violent and beautiful.

5. Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653): Strength in Strokes

Gentileschi, one of the few female Baroque masters, used oil to paint women of power—often survivors. Her brushstrokes are bold, her colors rich, with oil letting her make flesh look tough, not fragile.

Masterpiece: Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614–1618). This brutal scene (Judith beheading an enemy) is unflinching. Oil makes the blood glisten, the muscles in Judith’s arms tense, and her face determined—no softness, no apology. It’s a statement: women’s strength, painted in oil.

6. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675): Quiet Drama in Light

Vermeer was the opposite of Rubens—he painted stillness, but with hidden tension. His oil works use “camera obscura” (a primitive lens) to focus light, making everyday moments feel sacred.

Masterpiece: Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665). A girl turns, her lips slightly parted, a pearl glowing in the shadow of her ear. Vermeer layers thin oil to make her skin glow like candlelight, and the blue turban (ultramarine, expensive as gold) pops against the dark. It’s quiet, but you can’t look away.

How to Read a Baroque Oil Painting

Follow the light: The brightest spot is where the artist wants your eye—usually the most emotional moment.

Check the hands: Baroque artists used hands to tell stories (Caravaggio’s reaching fingers, Gentileschi’s gripping knife).

Feel the texture: Thick impasto = energy; thin glazes = softness or intimacy.

Pro tip: Visit a Baroque gallery with a small flashlight. Shine it on dark areas—you’ll see details hidden in the shadows, just like the artists intended.

Table: Baroque Masters & Their Signature Moves

| Artist | Nationality | Key Oil Technique | Iconic Work | Why It Shocks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caravaggio | Italian | Tenebrism (extreme shadows) | The Calling of St. Matthew | Makes holiness feel gritty |

| Rembrandt | Dutch | 30+ glazes for emotion | The Night Watch | Turns a militia into a drama |

| Velázquez | Spanish | Blurred edges (soft focus) | Las Meninas | Bends reality with a mirror |

| Artemisia Gentileschi | Italian | Bold impasto for strength | Judith Slaying Holofernes | Paints female power unapologetically |

Baroque oil painting didn’t just decorate walls—it made people feel. These artists used oil to turn paint into passion, shadow into suspense, and canvas into a stage. Even today, their works don’t just hang in museums—they roar.

At theArtPaint, we know the best way to understand Baroque is to stand in front of it. Explore our guide to “Must-See Baroque Oil Paintings in Europe” or try a DIY chiaroscuro sketch to feel the drama yourself.

theArtPaint.com—where Baroque’s fire still burns.