Edgar Degas: The Realist Master Who Captured Movement in Oil – His Life & Art

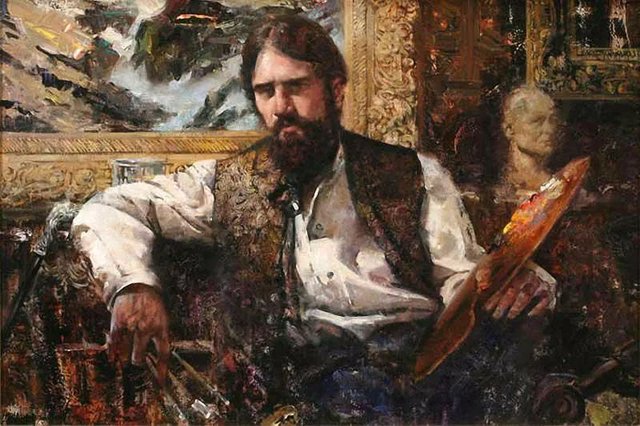

Edgar Degas stands apart in art history as the master of capturing movement. Born in 1834 in Paris, this French artist blended classical precision with modern observation, redefining how Oil painting could depict the energy of everyday life. Though linked to Impressionism, Degas called himself a realist—and his focus on dynamic scenes, from ballet dancers to horse races, made him a true innovator of oil’s expressive power.

Early Years: From Law Books to Paint Brushes

Degas grew up in a wealthy banking family, but his passion for art clashed with his father’s wish for him to study law. In 1853, he enrolled in law school in Paris but spent more time copying paintings at the Louvre than studying legal texts. By 1855, he abandoned law to attend the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied under Louis Lamothe, a pupil of the great neoclassical artist Ingres.

Ingres’s advice—“Draw lines, young man, many lines”—shaped Degas’s career. From 1856 to 1859, he traveled in Italy, copying Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo. These studies honed his precise draftsmanship, a skill he’d later use to capture the fluid movements of dancers and horses. By his late 20s, Degas had traded historical paintings for scenes of modern life, setting the stage for his artistic revolution.

Revolutionizing Dynamic Scenes: Degas’s Oil Painting Innovations

Unlike Impressionists who painted outdoors, Degas worked in studios, focusing on controlled compositions that froze fleeting moments. His oil paintings of ballet dancers, horse races, and café scenes revealed a genius for capturing movement through careful observation and technical skill.

Degas rejected traditional “pretty” compositions. He used unusual angles—like looking through doorways or from balconies—and cropped edges, making viewers feel like they’d stumbled upon a private moment. In The Dance Class (1874), dancers stretch, rest, and practice in a cluttered studio, their bodies twisted in natural, unposed positions. This realism was radical: Degas showed the hard work behind ballet’s beauty, not just the glamour.

He also experimented with materials. From the 1870s, Degas mixed oil paint with pastel, creating rich textures and vibrant colors. He layered thin glazes of oil to build depth, then added dry pastel strokes for highlights, a technique that made his dancers’ tutus shimmer and horses’ manes look windswept.

Iconic Works: Degas’s Masterpieces in Oil and Mixed Media

Degas’s works bridge classical skill and modern observation. Here are three key pieces that showcase his legacy:

| Work | Year | Key Technique | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Dance Class | 1874 | Oil with pastel highlights, off-center composition | Captures the reality of ballet training, using dynamic lines and unposed figures. |

| A Cotton Office in New Orleans | 1873 | Precise oil detailing, natural light | His only work sold to a museum in his lifetime, showing modern work life with classical precision. |

| At the Races: The Start | 1872 | Quick oil brushstrokes, diagonal 构图 (composition) | Uses tilted angles to create speed, making viewers feel the thrill of the race. |

Each work reflects Degas’s belief that oil painting should “catch life in the act.” He didn’t idealize his subjects—he showed them as they were: tired dancers, focused workers, tense jockeys.

Practical Tips: Capture Movement Like Degas

Degas’s techniques can help any artist paint dynamic scenes. Try these steps:

Study anatomy for fluid lines: Degas drew dancers and horses repeatedly to understand their muscles and movements. Spend 10 minutes daily sketching people walking or pets moving—focus on how bodies shift weight and bend.

Use off-center compositions: Instead of placing your main subject in the middle, shift it to the side (like Degas did in The Dance Class). Leave empty space to create tension, making viewers feel the scene extends beyond the canvas.

Mix oil and pastel for texture: Paint a base layer with thin oil glazes (try burnt sienna for skin, soft blue for shadows). Once dry, add pastel strokes for highlights—this mimics Degas’s method of making fabric and hair look tactile.

Later Life: Overcoming Darkness with Color

In his 40s, Degas’s eyesight began to fail—a devastating challenge for an artist who relied on precision. By the 1890s, he turned mostly to pastel, which required less precise vision than oil. But he never stopped exploring movement: his late pastel dancers, with bold, sweeping strokes, are just as dynamic as his early oil works.

Degas died in 1917, leaving behind over 1,500 works. Though he’d once struggled to sell his art, he was hailed as a national treasure. His studio revealed hidden clay sculptures of dancers and horses—proof of his lifelong obsession with capturing motion.

Legacy: Why Degas Still Inspires

Degas taught the world that oil painting isn’t just about beauty—it’s about truth. He showed that everyday moments—dancers stretching, workers chatting, horses racing—are worthy of art. His mix of classical skill and modern vision influenced Artists from Picasso to modern photographers, who still use his “snapshot” compositions.

For artists today, Degas’s lesson is clear: observe life closely, draw relentlessly, and never fear showing the messy, beautiful reality of movement. As Degas once said, “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see”—and in his oil paintings, we see life in all its dynamic glory.